| NAME | Rafi Eryut |

| NAME PRONUNCIATION | 'rRAH-bee' |

| AGE | ~ 90 |

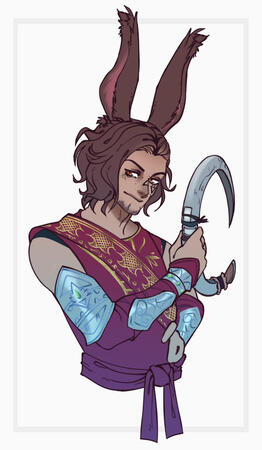

| RACE | Viera (Rava) |

| GENDER | Male (trans; he/him) |

| HEIGHT | 73 ilms |

| NAMEDAY | 12th Sun of the 2nd Umbral Moon |

| PATRON DEITIES | Minduruva |

| - | Nald'thal, the Traders |

| KNOWN OCCUPATION | Importer and jeweler |

| - | |

| PETS | Pipi, the family cat (pictured below) |

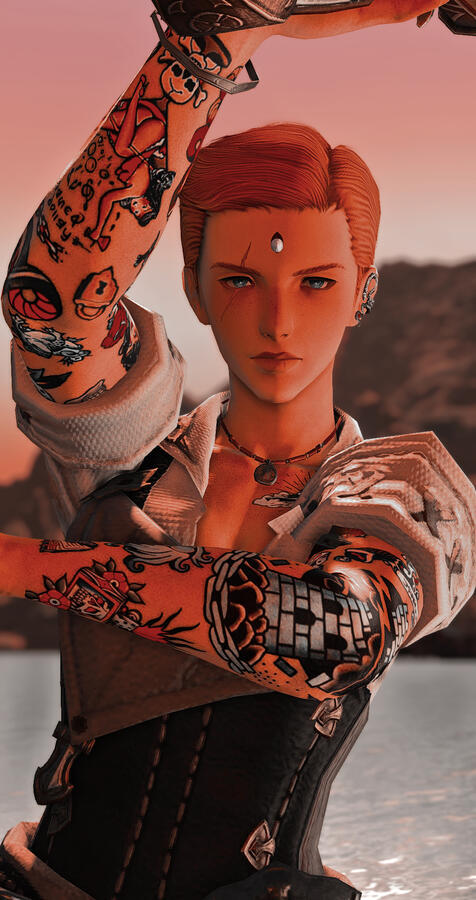

Youngest of the Eryut brothers, Rafi stands tallest, leanest, and most likely of the three to greet you with a smile and a silent wave. The Rava of his ancestral tribe sept have a distinctly leporine physiology, and Rafi is no different: he has a short tail, furred ear notches, and powerfully clawed feet. He styles his dark hair short to his chin, sometimes braiding a single tail and adorning it with wire or ribbons. A geometric tattoo—emblematic of some faded Golmore honor—runs from his freckled cheekbone down to his bearded jaw. It's a tidy beard, well-combed and oiled, like his brows—though after long travels his nape and sideburns run shaggy. Rafi's left eye is paler than the right, owing to some old injury or illness (he never specifies which).Catch him on a good night out with friends or family and he'll be dressed for the occasion in garments tailored for his lithe, firmly-muscled build. Not that he tries to stand out, mind you; in public, Rafi wears a calmer, observant mien, a contrast to his more pavonine siblings.

But he is by no means unapproachable. Often, he'll seek out the quietest person in the group—whoever's been lost in the conversation, or looks left out—and entreat them instead."You learn more about people that way," he remarks in his deep, lyrical voice. "And then you have a better handle on how much they learn about you."

FFXIVWrite 2022 Entries

II. BOLT

a glimpse into the high canopies of Golmore

above the territories and villages of Eryut

cw: mentions of drug use, foul language, physical violence

We have been up in this tree since peak-sun, us four jacks, and if my brother does not win this stupid competition against Arne I think we'll be here ‘til dusk.“Best two out of three,” he says, pointing at the slick, wet bark of the drommu tree. “We need more rounds to decide a true victor.”Arne has a look on his face I’ve seen before, the kind of suspicious grin we all get when my brother Refr is playing a trick. He argues that this has become an unfair game.“Who said this was a game?” says Refr, scanning our faces. No one speaks. That’s the problem, I think to myself: without meaning to, we turned it into a game. When the day's dawn rites were finished Uncle Skjol sent us up to the drommu canopies in pairs to gather sap. We filled a good six gourds. But then we found laughing kora growing along the tree’s eastern side, and things got silly. Most Rava chew the leaves for the full effect, but it gives me and my other brother Hrudr the strongest giggles when we rub the oil inside our ears.Refr isn’t laughing. He asks again, in what way is this a game? Arne rolls his eyes. “Your way,” he says. “You said, ‘fastest person to slide down the drommu and reach the next limb is the winner.’ Did you not?”“I did.”“Well, that is a rule. Rules mean you’ve made a game.”“Then let’s go more rounds.”Arne’s ears flatten. “Only reason for more rounds is if you don’t accept that you lost.”“I didn’t.”“You did!”I don’t interrupt, but, Serpent, I want to. This nitpicking is such a waste of time. The gourds are growing heavy on my shoulder, and the heat isn't helping. Overhead the sun beats like a salve-maker’s pestle, and it makes the drommu sap reek with a dark, stoat-y funk. We need to deliver them back home.Hrudr sounds fed up, too. “He hit a thorn, fridti*,” he says, his eyes a little glazed from the kora. “They’re all up and down the trunk.”“Well, I did not hit a thorn.”“It slowed him down,” says Hrudr. “They hurt like fuck. Not a fair go!”“Excuses.” Arne snorts. “Thorns or no, he is the one who’s slow.”Refr keeps a straight face as Arne carries on, and in spite of feeling irritated my heart twists with pity. Arne doesn’t know what he’s getting into, challenging Refr like this. He is three summers younger than us, just come to the treetops this spring. With him came an unbelievable ego. His father was our mother’s wife’s uncle, and by all legends was a fantastic jumper. But he wasn’t the best. Up here, no one can hold a candle to Refr, who is already tightening his greaves. It’s practically nenna.** Who will tell him he should keep his dumb mouth shut?Not me, I think, knowing that if not for the kora I certainly would.We gather at the limb’s edge. As we peer down the drommu–such a wide, ancient monolith of a tree, with some four-hundred yalms separating our branch from the ones below–we can track the natural grooves worn in the massive trunk. The perfect depth for a Rava to use for a vertical slide. Along each groove are fat, pale thorns finning out from the sap and moss. They’re as big as a hindfoot. My brother is lucky it didn't tear off his tail.“One more round, fridti,” says Refr, pointing at the lower limb. “Winner gets to say he’s best.”“And the loser?”“Loser eats bark and shit.”Arne spits out a bluish wad of kora. He rubs his hands together and squats down, ready to leap. “Loser eats shit.”Between the heat and the kora, I’m dizzy. I hunch under the weight of the sap gourds and laugh out something I shouldn't. “Look at you,” I say, pointing. “Do you always crouch like you’re ‘bout to take one?”I don’t hear what he says, but Hrudr does, and from the look on his face I know in an instant it was something very stupid. Hrudr dares him to repeat it, and foolishly Arne does–at a volume where all three of us can hear him: “I’ll take one down your throat.”"Why, you little–"Immediately he’s over the limb, but not from a well-timed jump. Refr kicks him hard. My stomach yanks and Hrudr grabs me in shock.“Refr–no!”We scramble to the edge. The kora spins my vision. It takes a few seconds to realize that Refr has leapt after Arne and caught him mid-air. Both are plummeting, shrieking, one snared tight in the other’s claws. We watch in horror as they streak down like a brown-tailed comet. They hit the branch with an echoing crack.We are not jumpers, Hrudr and I. Even if our ears weren't greased with kora we would have taken a long time to climb down. When we finally land on the branch, we see splintered, shattered stretches of drommu wood. A minor miracle: neither my brother or Arne are hurt. In a small splintered crater, they're both standing upright; Arne flails, loud and screaming, but Refr is grinning. He must have landed feet first with Arne hoisted up over his head.“Well done,” I hear him saying–now, juggling Arne above him, he is laughing–“well done!" As Arne stares down at him, his mouth flapping open like a broken hinge, Refr clarifies, "for not pissing yourself on the way down!”Before Arne can answer, Skjol is there. He's a small man, but the kora makes him big and impossibly angry: he's yelling, cursing, swinging something at us. All six sap gourds beat around our heads like angry bells. Hrudr and I drop to the bark, cowering. We had left them up on the branch above.By sunset, Skjol has dragged us home. All the other Warders eye us as we trudge into camp; they know we've been trouble. Arne gets chewed out for his arrogance, and for forgetting the sap Hrudr and I receive a full fortnight of our least favorite chores: laundry, spearfishing, and tick-pulling. Only Refr goes without punishment. I see him at nightfall with Skjol, muttering over supper. Skjol looks over at Arne, who is sitting by the firepit, glowering at his empty bowl. He shakes his head.It's the last time Arne ever challenges him. The next day, he hands his greaves over to the quartermaster and asks me to help him string a new bow. As we sit in the shade, I pull tight the sinew and show him how to loop it tight in the groove. I study his young face and think about how he looked as he fell, his eyes white with terror. How he kicked when Refr held him aloft, like a newborn babe.Smiling, I pat his hand, and hand him the strung bow.I don't feel bad for laughing.

*fridti – noun. A male relative within an Eryut members’s age or generation; a friendly term for a male or masculine-presenting citizen of Eryut, ala “cousin”

**nenna: – noun. An Eryut word used to describe the current social milieu among a group of Viera; a colloquial term for ‘the way things are.’

V. CUTTING CORNERS

from Houses Red and Chambered

a storyline about three brothers and their home in Kama

Because Refr was coming home, they bounded into the kitchen to make idlis. Each brother hauled a pot out of the pantry, rice for Rudi and dal for Rafi, and they took turns measuring out each ingredient in eight-onze scoops. “Four to one,” said Rudi, pinching rock salt from a wooden bowl, “that’s the ratio.” He stopped to tie a kerchief over his dark, wild hair. “And soak ‘em for an hour.”"You sure you wanna cook?" Rafi asked, digging in the spice cabinet. "He's just gonna wanna go to the Meyhane.""Fuck that. I don't have any gil."Rafi shrugged. "Neither do I.""So we cook." Rudi hosed off the idli tray, wiping down each smooth recess in the metal. "After all, that dal was gonna get stale."The little can of fenugreek was empty. Rafi trekked across the street to the spice shop to get more, but there was a line, and the vendor, flustered by the heat, misheard his request: he came home with a tin of hard, yellowish seeds. Rudi uncorked the bottle, sniffed, and laughed. “She gave you mustard.”“Can we still make them?”“We can make anything.” He handed Rafi a pestle. “Start grinding.”Rafi followed his instructions to the ilm. When the batter got too thick he ladeled in tiny spoonfuls of water; when it thinned out, he stood at the ready with clumps of drained rice to thicken it back up. Rudi stirred the batter with his hands, chopping and churning it. He flicked a milky glob of it into a chipped whisky glass full of water, and when the glob floated to the top they cheered.But the first batch came out flat and tasteless. They hunched against the counter, dunking each limp, fluffless idli into every oil and sauce they could find. Nothing, not even Rudi’s green mango chutney, brought them to life.“What did we do wrong?” asked Rafi. “Was it the mustard?”“No,” muttered Rudi, lifting the lid and peering down at the batter. “It’s my fault. I left something out."Rafi stared. "You what?""An important ingredient.”“Which one?"“Time.”Rudi lidded the batter and washed his hands under the spigot. Rafi followed him onto the terrace, where the peacocks were sunning; he shooed one off a chair, checked for bird shit, and sat down. Agitated, chewing on his lip, Rudi started doing chin-ups on the pergola bar, his lithe arms winging out with each pull. It was half-past noon, and sweltering.“You're s'posed to let it ferment,” Rudi said after his fourth repetition. “The batter–it has to grow.”“Grow?” Rafi scratched his jaw. He stared up at the vines blanketing the pergola trellis. “Like, mold?”Rudi snorted. “No, dumbass. It puffs up.”“So, like bread.”“Yeah. I thought we could skip it, but, nope. That’s a corner you can’t cut.”“So what do we do?”“Let it sit. Come back later.” Rudi grunted, his back straining. “We can go down to Splendor and get a coffee.”Rafi rolled his eyes. The Splendor was a snack stall near the villa, and while it had the best food on its street it did not sell coffee. A pretty girl had started working there on weekend afternoons. "How long do we let the batter sit? Refr will be here by seven bells.""It'll be done by then."Rafi sighed. "Are you sure?"He was; as they walked to the Splendor, he kept insisting it would only take four bells for the batter to rise. When Rafi tried to take a right at the fountain, Rudi swore they were supposed to go left. Soon they were lost. They knocked on the gate of a tidy blue house and asked for directions, but the gardener sent them on a choked, narrow street that dumped out into Artha. The city square was unbelievably busy. Freight wagons streamed along the thoroughfare toward the Crucible, and the noise of their wheels rattled above loud lunchtime crowds.Rafi's ears flattened. The air had a heaviness to it, a prevailing urgency: everybody had an errand to run, a place to be, except for him. Around him, people surged. He turned to Rudi and pleaded to go home. But Rudi stood in the stream of foot traffic, unmoving. Passersby diverted around him. He was smiling up at the city overpass, where a tour of gaja-riders were crossing a painted bridge.Rafi stared at his brother. A big man jostled him, and he felt a nudge to his hock from a passing woman leading a clump of noisy children. But he waited for Rudi to look away–eventually the gaja moved off the bridge–before taking his arm. He pulled him through the crowds until they were safely out of the square.It took another bell to get home. In the kitchen, a pale, creamy puddle oozed over the counter: the fermenting batter had blown off its lid. Tears stung Rafi's eyes, but then Rudi made a lewd joke that sent them both into a fit of laughter. They were doubled over and howling on the kitchen floor when Refr walked in."The ship was early," he announced as they scrambled to their feet, and, just before they rushed him with arms open, "shall we go to the Meyhane?"

Tales from Golmore, and After

The SentimentalistA Viera's memories of Golmore can be tiresome, complicated things.(content warning: violence, mention of torture/physical harm, insects, descriptions of death, body and gender dysphoria, smoking, alcohol use, heavy emotional themes)

Houses Red and ChamberedRafi moves into a new home in Ul'dah. Some strange and frightening things might be moving in with him, however...(content warning: heavy emotional themes, disassociative and surreal moments/scenes, eerie/creepy imagery)

Part I

The winged woman was pressed against the wall of his office when he woke up that morning. In the weak Thanalan light he stirred, rubbed his eyes, saw something bleary out of their corners and realized a dark thing was lingering beneath the high windows. An inky-dark shape against the wallpaper, like an untreated stain. He sat up on the loft cot and rubbed his eyes again. When he opened them he knew it was that same woman, here in his room, again. Staring at him.This time, like last time and all times before, her mouth unfurled like a red flower, opening.Rafi swung off the sofa. He grabbed his chakram and turned around but of course by then she was gone, whoosh, just like that–the corner empty, the stone unperturbed–and because she vanished so fast the chakram had already left his fingers, thrown. It clanged on the wall, bounced off, whizzed over the railing, and landed somewhere downstairs below the loft.“Thal’s balls,” cried a voice. It was Memela, back from the airship landing. She had just come in, and though he couldn’t see her he knew what she probably looked like down there: slack-jawed, bug-eyed, startled by the noise. Probably towing a handwain heavy with wooden crates.Rafi sunk back onto the sofa. He rubbed his face; he was out of breath. His chest felt like a steel drum, a pressure pushing out from inside.“What happened?” Memela was jogging up the loft stairs two at a time. “What was that?"“Saw a spider.”“You did not.”He said nothing. There was a pitcher on the coffee table nearby; he got up, filled it with water from a wall spigot, sloshed it around, poured it down the specimen sink, refilled it, and drank. Memela glowered at him from the landing in disgust.“You look like shit,” she said.“I know.”“What happened?”“Three-bell delivery. Didn’t sleep.”Memela threw up her stubby hands. She clomped down the stairs, slipped past the specimen shelves, and rounded the front desk. There was a logbook in the top drawer and she set it on the desk with a leathery slap. “I’m sending you home. I’ll get Barty down at the Exchange, he can do the potsherds.” He heard her pen-tip clinking against the inkwell. “Don’t come back until you’ve slept."“No.” Rafi lowered the pitcher. Water ran down his chin. He was dizzy; he put a hand to his forehead, as if to steady himself. “Don’t call Barty. He always fucks everything up–”“Enough.” He heard Memela shut the logbook. “I don’t wanna hear it. Pack up, grab your cat, and get out. Am I clear?”“Yes ma’am.”“Show up before tomorrow morning and I’ll put you in an urn. An ugly one, too, something you’d be embarrassed to put on a mantle. You got a new house, Rafi. You got a raise. I hope that means you got a new bed. Go sleep in it. Is that clear?”Rafi slunk down the loft stairs. She was standing on her footstool behind the front desk, palms spread on the counter, gold eyes glowering at him like a wary cat. Like the quartz chunks peeking out of the wain crates, Memela Mela was always crystal clear.Ten minutes later he left Office 8 with his coat, work-sack, and the soft-bodied cat satchel. It was a quarter bell’s ride from the chocobo porter station in the Exchange down to the Goblet bridge, almost another quarter for the ‘bo-wagon to navigate that high, suspended road that led to his ward. But from the brass gates to the main thoroughfare to the narrow, shadowed cobblestones of the residential district, he let the cat out of his satchel and loped the five-minute walk from the ward entrance to the front steps of the house in Irontree Court. The house was baking under the rising desert sun, the stone walls catching shades of umber, charcoal, bright burnt orange. A cluster of pigeons took off from the red clay roof, mourning for shade.This was his house, he thought as he worked the key in the hanging brass lock. He opened the door and allowed the cat to sneak ahead of him, slithering into the foyer like a tiny ghost.

The house had come furnished. Across the level span of tile flooring the company agents had placed a motley mix of mismatched pieces, stone tables and copper screens and chairs carved from desert ironwood. There was a shiny red wallpaper. Linen curtains hung above felt rugs, and when he turned the kitchen spigot it sluiced out hot water that splashed musically over pearly stones mortared along the basin sink. He liked to run his fingertips over the stones with the water running, imagining a stream, but then he remembered how high Goblet utility fees could get, and cranked the spigot shut.Downstairs, the bedroom: the only room in the house that wasn’t some shade of desert crimson. He holed himself up behind the big wooden door, tuning down the sconces until the room glowed a cool yellow-grey. The cat had a cushion but always slept at the foot of the bed, coating the bedspread with pale, skinny hairs; Rafi sat to take off his boots and got up cursing, dusting off his backside. What kind of man wears all black and owns a white cat?

“I do,” he said as he wandered past the closet. The bathroom’s azure-blue felt oppressive to him, like deep water. After scrubbing his teeth he stood and stared hard at himself in the oval mirror and wondered how anyone could have abluted themselves in here and felt clean.He flicked off the sconces. In the blackout-curtained dark he lay on the cool bedspread, and his ears relaxed until they hung like furred ribbons over the pillow. He closed his eyes.She hadn't appeared in the house. So far she came only when he was at work, when he napped, or during snatches of sleep aboard airships between stops. He made the conclusion that she must be a recurring dream, a waking lucidity who, if he tried to explain her, would prove more cumbersome than simply enduring her presence. So he endured it. He made excuses for her: she was his sleeplessness, his overworkedness, his finger-wagging guilts; she had only been showing up for a fortnight, and not every day; he had so much on his plate that there was no room for her, and she would eventually slide off. A passing dot on the horizon.

Sleep brought back an old dream with a new face: Lejo. They were looking for a cobbler in the Muthru Bazaar. He was leading the other man by the hand, winding past stalls and market stands and sweaty rows of scarved merchants.You used to live here, said Lejo.I did, Rafi replied. A bell tolled above the din of the crowd; it was like no bell that ever rang in Rabanastre. He sensed that the cobble street had blended with the sandy bricks of the Sapphire Exchange, shimmering together in that hazy, fluid way that only happens in dreams. A seamless marriage of old and new.How did you not get lost? Lejo asked.We did. We always got lost.Always?Every time. It was the smell–everything smelled like nothing I’d known before.How did you figure out where to go?How does anyone, when they move some place new? You simply do.Smiling, Lejo scratched his neck. He had a fistful of pumpkin seeds, glistening green pepitas with shells like olive-colored jewels. Rafi looked ahead to navigate, but he could see them; he couldn’t take his dreaming eyes off them.I want to buy you everything in this market, he thought, and Lejo heard him think it without replying, still only smiling. Words boiled out of him. Those earrings, these figs. Blue silk and red kidskin. Every flower in every vase. Back then he didn’t know what a samovar was–he had to get Refr to write it in runes, then in common letters, then say it out loud, syllabically–but as they passed the tea-seller he suppressed the aching urge to pick one up and cradle it into Lejo’s arms like a brass-wrought lamb.They couldn’t find the cobbler. “Who else can properly fit boots to Viera feet,” Lejo said in his brother’s voice, but which brother it was he couldn’t say. The market sounds blackened to a dull, thick silence. Crowds so loud and oppressive that the dream rendered them silent.At the cool, shaded end of the street there sat two hulking ravens, their wings flared open like scarecrow arms.His chest felt suddenly compacted, the bindings vice-tight. Lejo was at his left arm, tugging his sleeve. “Not here.”One of the ravens clucked, walking in that strange, bobbing crow-manner that distinguished them from hawks. It had no eyes. Then it had dozens of them, each opening like black antlion pits sucking through hell-colored sand.All staring at him.He turned and broke into a sprint, dragging Lejo with him. Agony sung through his lungs. Past the stalls and bakers and crates and hoopers and barrel-laden mules, over clay walls and around cisterns, diving down back-alleys thick with dust and grease and pickpockets. Every door was shut, locked, barricaded, no entry. Fast as they ran, there was nowhere to hide.Of course, she would have eventually found him here. Of course, no crevice of memory, however innocent, was safe from the woman with nightblack wings.

The linkpearl roused him. It was after noon.Aching, he sat up, felt around the bedside table, knocked the pearl off, hoisted himself over the edge of the bed and palmed around for it on the floor. He switched it on and pressed it to his ear. “Hello?”Silence. Weak static fluttered on the other end.Rafi sat up. Cold swept his limbs. He licked his lips and repeated, “hello? Is someone there?”“Hello!” A male voice, deep and merry. “Good afternoon! My apologies, I wasn’t sure if the connection had properly gone through.”“Who is this?”“My name is Pointenloix, good sir, and I am an associate arbiter with the Adventurer’s Guild.”“I don’t know who that is.”“I herald you from Ishgard, good sir. May I speak to Reffer? Reefa”–the merry voice hesitated, struggling to pronounce–”how is it meant to be said, Reffa–?”“Refr.” Hastily Rafi repeated the Rava name. “‘Rayv-ish’ is how you pronounce it, and no. This isn’t his code. Why are you calling?”Mumbling on the other line. “Apologies, I seem to have rung up an incorrect code–”“Where is Refr?” Wincing at his own tone, he added gently, “I’m his brother.”“Ah, a next of kin! Well, that’s particularly to my benefit. You see, I’m calling because of an arbitration request, one levied against a free company in accordance with our inactivity clause. This company was previously listed under your sibling’s name…”The man began to ramble. Rafi interrupted him, tersely insisting to know where his brother was, only to be told that was the problem: nobody, not even the staff at the free company’s estate, seemed to know. Nobody had been in contact with the administrators for the past two moons. A strange situation, these unannounced departures. But no complaints from the estate itself, all seven of its staff. They arrived the previous sennight to find their services paid in full for the next six moons.“But you don’t know where they are,” said Rafi. “Either my brother, or the other administrator. You called me, thinking you’d find them.”“Yes, that’s right.”“How did you even get this code?”“It was listed on the company file. Listen, would you consider checking in with the Guild office nearest to you? Wherever you are, Gridania, Limsa Lominsa–”“Ul’dah.”“Yes, fantastic, perfect–if you could stop by the Guild offices within the sennight and verify your information as a secondary contact, we can drop arbitration and renew the license for the next half-turn. Would be best if you could make it up to the estate proper so that we can validate continued operation or at least progress to discussion of sale–”“Right. Sure.” Rafi switched on the bedside lamp. “It’s in the Quicksand, right? The Guild office.”“Yes, that’s correct.”“I’ll swing by. That’s all they need, then? My, uh. Information?”“Your name and address. I presume you have the latter?”Rafi stared at the ceiling, all sandstone and shadowy timbers. “Yes, I do.”“Perfect. Again, thank you for your assistance, we’ll be in touch again soon.”He set the linkpearl on the bedside table and flattened his back against the bed. The sun hammered a narrow ray of gold light through a sliver in the blackout curtains, and in that ray the cat had stretched out, gone long and white and liquid under its glow. Rafi chirruped to him and patted the bedspread. The cat did not, would not budge.A cold ache spread up from his belly. He wanted to see Lejo. At first he swung a leg over the bedside, his rabbity foot spreading out toes the cool tile floor. But he reconsidered, and rolled back over. The bed had a second pillow, around which he threw his arms and bundled close. It smelled like linen, soap, dry old rooms. Hints of sun-bleach, from hanging on a clothesline.The dream. He thought of Lejo in the yard of the Bole, digging, dirt up to his tawny forearms. Far above the roof’s silhouette he imagined the Thanalan sky grey as steel, hot with sun but cold in color. Back when he and Mayvis had trekked through snowdrifts knee-height and higher to look for him in Garlemald he’d marveled at how dark it got, how vast spans of snowfield shivered blue-black beneath the lightless evening wind. A land for jailers, grated with galvanized sorrow.He released the pillow. No, he couldn’t go to Lejo. Not about his brother, nor about the winged woman. Sighing, Rafi yanked back the bedspread and stuffed his legs under it, his calves swiping feverish against the chilly linen. It wouldn’t be kind and it wouldn’t be right, harassing that sweet man with these phantoms. Gods knew he was running from quick-leaping ghosts of his own.

( part II soon ! )

Part I

There was a tree of memory. It grew wide, tall, and impossibly green. During the day it poured shade over a wooden pavilion in the village of Eryut, and in the middle of that pavilion sat a narrow bench. The bench belonged to Maja. Long ago, the women had built it for her, a place to sit, teach the village children, and listen to the Wood.She was their grandmother, maybe. Neither triplet knew for sure. To Rafi, the memory was very old: she was smoothing black clay over their small, blistered hands. In summer Golmore sweltered, but the triplets–Hrudr, Refr, and him, little Hrafn–huddled close in spite of the heat; the air smelled hot and woolly, like unwashed hair. The clay was cool and tingly. Traders had come with goods from a place called Isari. They had also brought some fruit that had a bad oil in the rind, which gave all the babies a rash. Beside him, one child complained, “Maja, I don’t like it. It stinks.” Her gnarled voice crept into their ears as she sang. “Serpent, Serpent, take this itch away.”Her voice, her hands, the tree: she always came back to him in that order. Her fingers reminded him of oak roots–a cliché likeness, maybe, but one that no child would have spoken out loud. Trees were sacred, like women, above and beyond comparison. Trees gave the Rava everything: shelter, food, water, Mist, guardians, even the air they breathed. And because she so often sat beneath it–and because that generation of the Eryut tribe was unlike its predecessor, ceremoniously strict about preserving nenna–everyone, even the matriarch, called that one Maja’s Tree.

Radz-at-Han, six summers ago

“–and she is dazzlingly beautiful.”Laughter, music, rubies winking through floral smoke: They were on the veranda of his villa, he and Taruna, looking at jewelry and sharing a pipe. She was the troupe’s new principal dancer, and needed accouterments for an upcoming performance. And he, taking a sabbatical from the import business, really needed the cash. So he invited her over to pick over some of his latest work. The jewels charmed her; he was charmed that she found them charming. Years ago, they had danced together in a different troupe, and she was delighted to have him all to herself again, even for just an hour. Rafi indulged in it. In that big, lonely house, absent of his two brothers–Rudi gone, training in Rhalgr’s Reach, and Refr, well: who knew where he’d dragooned off to–it put him at ease to hear a woman laugh.“Oh, Rafi,” she sighed, sinking into a cushioned chair. “So sentimental. I never knew you cared so much.”“Yes, you did.” He carefully boxed her bracelets, setting them beside her before easing onto a nearby divan. “Remember The Sylph? Your little smile at me during the développés used to yank my heart right out of my chest.”“I wish you’d have told me.”“Wishes and wants.” He glanced skyward. It was a splendid evening; frogs chirped in the silk trees, which were fragrant with pale pink blossoms. Below them hummed the city, huge and sonorous with life.Taruna grinned behind the long pipe stem. “Want to see my other new treasure?” He barely had time to say ‘sure’ before she thrust the pipe in his hands, bounding up off the cushions and hiking up her blouse.“Slow down,” Rafi groaned, averting his eyes from skin, the oval curve of her breast. But he gasped when he saw her tattoo, a brilliant blue peacock in full feathery display over the slats of her ribs. “Faram’s light,” he said, his awe genuine. “How many days did that take?”“Two, six hours each.” She shut her blouse with a soft snap. “Do you have any idea how much it hurts after a while?”He did. He pointed to his left cheek with the faded markings, the simplistic pyramid of pips and tribal deltas. Hesitantly–he found it irritating to flip a conversation towards oneself–boyishly, he admitted that he’d grown up around women who had some very intricate tattoos.“Oh?” With slim, quick hands Taruna retrieved the pipe. She leaned back, fitting the mouthpiece between her lips, eyeing him. She could taste a story. “Like what?”“Well….”He tried to start off simple: he began with his mother, Bjelke. For protecting the village from a band of Bysnoe raiders she was bestowed a cuff of blackwork around her calves, and to honor her diligence in childbirth she bore three diamonds in a geometric spangle above her hips. The tribe's tattooist had encircled her breasts with a motif of the Serpent, blocky and gold, to match the bigger, older design limned across Maja’s back. That image wandered him into recollections of Maja and the sheer vastness of her; she, like many Eryut women, had comet-white hair so long that the braids dragged on the ground.Taruna listened, rapt. In the troupe, she had heard plenty of his adventures: about Nagxia, the river journeys, the brittle summers in Rabanastre, scraping out a living. But not the village. Soon he was drifting, rambling without realizing it, pouring out whole ewers of Eryut–the Tree and the warders, the elders and the canopies, the women and the terrors and the nenna and Mist.When he finished, Taruna was staring at him. At some point, the cat had wandered in. Scenting a visitor, he rubbed on her shins. She didn’t seem to notice, and slowly handed Rafi the pipe.“You must really miss them,” she said.Trying not to cry, he rasped, wholly unconvincingly, “I guess.”

Under her Tree, growing up, they ate the seasons. Summer fruits, autumn nut-cakes, pink winter sausages slivered with Golmore ginger. In the spring, The Wood brought levin-eels surging down the river, their bodies like wet crystal tubes. Maja cooked and fed them with her fingers, the eel-skin hot and crackling. “Refr,” she chided. “Not so many. Share with the rest!”With a village full of cousins they were never short for playmates. Games like coeurl-queen, ‘bo-and-rider, or hunt-the-flea could last for days. You couldn’t divide the triplets, though; if you played with one, eventually you got all three.“Cheater!” shouted Poln, a leggy child with spotted ears. They were squabbling over warbi, which was played with stones on a chalked grid. Hrafn, eager to win, had flicked a pebble into Poln’s eye.“It was an accident,” he pleaded, and it was; of the triplets, he was gentlest, and played fair. “I didn’t mean to.”“You lie!” Poln stamped her big clawed feet, braids bouncing. “I hope Maja spanks you!”Appalled, the triplets stared at each other. They could not fathom it. Only outsiders beat their young, and Maja had never so much as tugged their ears, even when they stole flatbread or put lizards in her piss pot. “She wouldn’t,” shouted Hrudr. But Poln fought dirty. A stone soared and–whap!–struck Hrudr below the jaw. Refr and Hrafn tackled Poln, thrashing and clawing and biting. Viera children had fangs for milk-teeth; their noses bled long after Maja pulled them apart.“Stuff them up,” she scolded, “and tilt your heads.” She was busy soothing a wailing Hrudr, rocking him and singing, “Serpent, Serpent, heal the pain.” So Hrafn took turns cramming river moss up his, Refr, and Poln’s nostrils. Poln scowled, and when Maja turned her back she blew a wad of snotty moss at his toes before storming away.

Nagxia, thirty summers ago

“So violent,” Cam murmured, lying beside him under the lamp and mosquito net. A flicker of her hair lay on his cheek; her bed was narrow, built for one. “All little girls were like this?”“All children,” he corrected her. His gendering of Poln in the story was retrospective; Eryuts did not use terms like ‘boy’ or ‘girl’ until after a child came of age. “We were rough sometimes. We had to be.”“Why?”Rafi considered. He had mentioned the Green Word before, but nenna was harder to explain. He likened it to a way of life: how some travelers talked about customs in faraway places. One village would do their nenna this way, while another, sometimes barely a malm away, would do nenna a little different. ‘The way things are,’ he elaborated, was an easy tradition to reinforce when everyone was so old and wise.“So what happened to her, this little Pola?”“Poln.”“Pol-nuh.” Cam caught on quick to Rava words and names. “Where is she now?”“I don’t know. Still there, probably, healing people. She was a salve-maker, like Maja, but she could still kick our tails if we pissed off her or her wives.”She rolled to peer at him, piqued. “Wives?”“Wives, four of them. Cielje, one of them, did leather work–she helped with my tunics. Why?”Now she propped up against him, searching his face with owlish eyes. “Why did she have so many wives?”“She wanted to,” he said, nonplussed, having never considered the question.“You could have a bunch of wives just because you want to?”“Isn’t that why anyone should have a bunch of wives?”Instantly her face changed, and he knew he’d said the wrong thing. Marriages were her family’s bane. Her father was a paragon in Dagluk–loyal, hard-working, a firebrand of a Resistance fighter–but, like many outsider men, he was constantly bested by challenges of honor. A rumor came wandering down the One that he’d fathered children with a baseborn girl in a town further down south, and refused to claim them.“Did you have wives?”Softly, testily, Rafi said, “You know I didn’t.”“Your brothers, then.” Cam chewed her fingernail. She suspected her uncle, bitter over politics, was behind the rumor, but he was doubtful. Nothing could convince him his own flesh and blood would bed with those Imperialist rats. “Did they have wives? More than one?”“It didn’t really work that way,” he said, so she rolled over, a sign that the topic was done.Night settled in, and it began to rain. He loved to lie in the dark and imagine the forest coming alive, the vines dripping, the broad fleshy leaves gathering water like green urns. These were kinder jungles for Rafi, benevolent ones; the trees had names like ‘tamarind,’ 'soursop,' and ‘frangipani.’ They wouldn't eat you alive.He stroked her cheek, ready to forgive her, but as she nuzzled her crooked nose into the pillow she said, “I’d rather hear about nice old Maja.”Rafi stared at the netting. It was a relief, loving a woman who could understand brothers: how they were so priceless, treacherous. Talking about the village gave him another feeling altogether. Some things were too brutal to share with Cam, too foreign. The same nice old Maja who predicted floods and levinstorms once punished a thief by stripping her down, smearing her in honey, and abandoning her to a riverbed full of chigoes. What would she think of that? If Poln and her sweet wives weren’t discussable, then what about her chubby babies, his nieces? Rudi wound up fathering three of them. Could she fathom his tenderness then?“I wish I could’ve met her,” Cam murmured, and soon she fell asleep, the whole notion already a dream.

Part II

Outsiders were inquisitive. They liked to contrast and compare.“Did you know some miqo’te men lived similarly, in the Shroud?”The Keepers, yes. He’d met some. There was a Host informant with a scalded tail who once fought Imperials on the Bozjan front: a wonderful fellow. Real genius with artillery, that guy. But it still wasn’t the same.“Well, then, what was it like?”Terrible. Next question.“What do you mean, terrible? Was it very dangerous?”Brutally so, cruelly. The Wood swallowed jacks like dodo pullets. There were beasts in that jungle, arcane creatures, entities of legend and nightmare. There were mantises the size of houses, hellhounds that reinvented the concept of hell. One season, a skeleton rose up from the dirt, cobbled together from the bodies of panthers that had died while feasting on men.Gods of the forest are monstrous gods. Anyone who believes otherwise deserves their doom.

The lower yalms of Maja's Tree were notched with heights of children grown and gone.“Come stand here,” she called, “the three of you. It’s time.” Their last measurement. The Phrygian knife had a gold handle, and Maja gave thanks to the Serpent with each careful notch. Bjelke’s triplets, finally grown.That summer, Hrafn was tallest. Doting and fawning, Bjelke wrapped her arms around him. She was dazzlingly beautiful back then, their mother, so tall and gloriously hirsute. Every time Hrafn glanced in a looking-glass he saw a similar jagged brow, almond eyes, and broad, hawkish nose.Bjelke’s good mood was a small blessing. Lately the triplets were insufferable, exasperating, the source of a thousand complaints: They stunk, ate more than goobbues, and quarreled so much that she wanted to chop off her ears. Hrafn hated to upset her, but Maja was right–it was time.The men would be returning, and soon.“You’re sure?” Refr asked later, clutching his shaking hands.“With all your heart?” Hrudr asked too, trembling beside him.Hrafn was; he had to be. The Green Word was a law that governed the body and the soul.With his brothers' words lingering in his ears, he went to Maja. As he spoke, she placed a hand on his shoulder. He pleaded, wept without meaning to weep, but already she understood. She knew what to do. She brought him a clear tincture in a tiny glass vial. She showed him how the salve-makers ground red pine bark and boiled it with nettles, and how he could bottle it for when he needed more. As he sliced off his plaits, the Phrygian blade snickered–snip! snip–and Maja buried them deep under the loam at the base of her Tree.“Hear me,” she whispered into the soil, digging her fingers in, reaching. "Great king of gold and wonder. Blessed jaws between which we rejoice. Holy teeth sent to devour us whole, hearken! See this man. Guide this man. Bless him and his brothers as they offer up to you." She reached out and pressed knobbly fingers into the back of Hrafn's head, bowing it. Serpent, O Great Serpent …That night, he lay awake, shivering. Maja, spinning brown wool in the hearth-room, told Bjelke what had come to pass.“Hrafn,” she said, “lives as men do, now. Do you know?”Bjelke said that she did.“It is for his brothers that he has chosen this. In your womb, together–in life, together. In death…” She trailed off. The spinning wheel creaked. “They won’t be parted, daughter. It is his will, and nenna shall shift with it. Do you see?”Frank, practical Bjelke. Her sigh, though obvious, weighed less than a feather. “Of course,” she said, and he imagined her shrugging, throwing up her big clawed hands. “I see! The nenna will shift.”“Good. Pass me the distaff.” A pleased grumble. “These cloaks won’t make themselves.”The next morning, the matriarch blessed it. Having no reason to protest otherwise—the village always needed more warders—the elders recorded it, gave praise to the Serpent, and went about business as usual. The men descended, wary as deer, and after Hrafn went up with them light and elated—feeling fit to fly in his new tunic and brown cloak—he soon learned the truth about their peril, their feral wildness. Their everlasting dance with fear.

“It was an honor, then–a triumph, to survive all that?”Sure, but why sugarcoat it? That was the Green Word, a Golmore reality. Sheer luck was the reason he and his brothers survived as long as they did. As for honor, well, that was the purview of women. Their father died long before they learned his name.“And this Serpent–”Ask Maja. Jacks weren’t qualified to answer. It was the elders who revered the Wood guardians, elevated them to Rava godhood. And Maja, their faithful haruspex: her answer was as good as gold. She communed with meat-eating flowers to predict coeurl-queen weather, and she could tell if malboros were breeding just by examining the innards of a vinegaroon. It was possible she spoke directly to them, in the Old Tongue–which, according to Rava legend, could intercede to diresaurs and wyrms.“But what was the Serpent?”What is greatest? Ask that question, and its answer provides. The otherworldly Serpent: to Eryut, it was their sun-bright executioner; their priceless jury; a history of hungers, that all-consuming judge. Every Viera knew its shadow. Men were honored to die by its fangs.“To … die?”Yes. They died. The end.Where on Eorzea is there a story that keeps going after death?“No small wonder you left.”Silence, hard and oaken. Every time a conversation wound its way to this point Rafi would run a callused hand through his hair and blow out, whoo-hah, an anxious breath.“No small wonder—”Smiling, as pleasantly as he could muster, he would say, “could we talk about something else?”

Ul'dah, two moons ago

“I don’t remember a cloak.”The admission caught Rafi off guard at dinner. Around them, the Quicksand was noisy, boisterous with levequesters. They had been drinking, the brothers; Refr, lolling in the enameled chair at the head of the table, was eating off a plate of honeyed figs. He repeated himself: he did not remember the villagers sending the Warders away each season with new cloaks.Rafi scratched at his beard. “You don’t?”“No. I believe you’re mistaken. The women never made us any clothes.”Rudi chimed in beside him. “Maja did.”“She did not.”“She did!” Rafi peered at Refr, incredulous; he could not tell if his brother was feigning forgetfulness for a lark. “One for each of us, gray and brown! It lasted for summers–or, at least mine did.”“Well, good for you.”“I don’t know why you’re being so sanctimonious, Refr.”“Whatever could you mean?”Rafi chewed his lip. His ear flicked irritably, and under the table he bounced one knee. "What do you get out of pretending you don’t remember? It’s not like you could actually forget.”Refr smiled cunningly. He pinched a tuft of saffron over his figs.“It’s not?” he asked, sending an inchoate chill up Rafi's spine.Deep into his sixth beer, Rudi set his huge hands on the table. He gestured while he spoke. “Speaking to the era in which I believe dear brother is referencing,” he drawled, “in the canopies, gear was awful. I remember it, as I recall, it was all bought, borrowed, or stolen. Especially metal. Gods, a real miracle they had up there in Ishgard, wasn’t it? All that steel. Can you imagine if we’d had that? Not even Skjol, that rat-bastard–” he wagged a finger “–blast that stupid old jack, had greaves that fit his fat hocks.”“Who?”Now it was Rudi’s turn to gawp. “Uncle Skjol?” he shouted. “Our mother’s brother? Or, wait–was he Djura’s mother’s brother–” He lost track, fumbling fingers, struggling to count genealogies through the haze of beer. “Or was it … hells, I don’t know.” He hiccupped. “Gods-damn, brother, will you stop looking at me like that, Refr? Come now! You snake–you’re playing dumb just to rile us up, you rat–”Rafi rose from the table. “I’m going to have a smoke.” He winged outside, paced down the Lane, and then stopped to press his back against the wall.He looked up. A few stars crept into the desert dusk, little glass-shards of light through the city’s glow. Lively black shadows ascended above as a clump of oily-winged starlings flew past the wall. They disappeared behind an edifice, and the sky was still.It was pathetic to him sometimes, this routine of theirs. Even if the pattern was timeless, its steps were exhausting, a constant fraternal fight: adore, follow, question, bicker, fight, forgive, repeat. He thought about storming off. But there, in the evening lull–in that dull, aching space between anger and love–he caught his breath. He lit a kretek.When he finished, he slunk back to the tavern, his hurt shed behind him in the alley, like an old skin.

Part III

Refr, though–there was the crux of it. The part of the performance with the dramatic pause: ‘and then, Refr.’ Every step he took was so calculated, so planned and carefully thought out. If he annoyed you, it was because he meant to annoy you. And he was good at it. He played mental chess; he over-under-overstrategized; he nenna-ed to the tune of his own drum.Sometimes it astounded Rafi, how well his brothers took to the ways of outsider men. So many of their male comrades subscribed to the belief that tough things were best handled by not really handling them at all. Or by destroying them, which was bad, almost worse. Rudi could grin and punch through life, but Refr devoured it. He thrived and excelled at it.Refr, named for the fox. Refr: the sly one. Sixty summers since they were exiled–living between kingdoms and cities and slums and palaces–and he was still most at home five fulms up his own princely ass.“…exiled?”

Oh, the last time they saw her. The blood-warm night at the end of that horrible day. They had raced down from the canopies, him and Hrudr, tearing over roads and bridges. He couldn’t speak; he ran until he panted, his throat searing, sore lungs pumping for breath. Frantically they loped ahead of the other Warders, who did not yet know what had happened, to save their brother from the villagers who, through the Mist, surely already did.Two guards caught the brothers at the gate and dragged them in by the arms.Hrudr thrashed. “Where is Refr?”“What happened to him?” Hrafn added, struggling, dreading what they might say.The guards did not answer. Mothers were coming out of their houses with fat babies on their hips, while groups of gangly children gawked at them from behind bushes and stumps.Maja was on the pavilion by her bench, wide-eyed. Her hair beat wild around her in sheets.“The Serpent,” she shrieked, anguished. “The Serpent! Is it true? Is it true, did it–did he–?”Her hands. He saw them in great detail then, like a lens flashing up close. Raised, narrow, wandering sinews made the most perfect circles around her knuckles. Tiny spots, each vaguely translucent, bloomed above her plum-colored veins. Her palms were like the skin of an onion, so thin and crinkly fine. The talon-nails, dark as bruises, were limned with dirt.They were grabbing him, shaking him, cursing him and his brothers.These, the hands that had given him life.

“So you didn’t leave?”Silence, again.“You were exiled?”Nothingness. A vast, unavailing blackness. The Wood is not a quiet place, but on that night–the night of Refr and the Serpent–he could hear nothing. Not even his own pulse.“But what happened with the Serpent?”Now it drummed like a hammer in his ears.“What did you do?”Nothing."What did he do?"

There was a tree. Several of them, actually. If you mapped them, the dots would span the realm from east to west.There was a date palm in Yedlihmad, a silver laurel in a field below the Abalathian foothills. He once visited cedar saplings freshly planted in La Noscea, their tiny needles fanning out in the breeze. Columnar pines, waxy-leaved apples, persimmons overburdened by fruit: there were so many. He even once did it under a wiry, winding, spindly larch jutting over the salt rock shore north of Shoal Rock.From Kugane to Coerthas, Gangos to Gridania, they all sufficed, when he needed a tree.This is what he did: the thing nobody knew, not even his brothers. The little ritual. He went to each tree and put his hands on its trunk. He touched the bark, examining for sap, splinters, stinging caterpillars; carefully, almost lovingly, he brushed away the moss. He put his forehead to the bark. With his eyes closed, he would lean there, touching the tree for moments, minutes, long meditative hours–sometimes only a second. It depended on how badly he needed it. Needs like this are timeless. One day he may stand there for days.He would let go. Sinking down the side of the tree, crouching and squatting, hunching over the imprecise space where the tree met the ground, he’d wait. If there was undergrowth, he’d part it, mindful not to uproot anything vital. The moment his fingers touched earth, however, he began to dig.Serpent, serpent…A lot depended on the soil. The dirt and sand–it could be both, or very rocky and dusty, stubborn with pebbles–reached further up his fingers. His forearms were umbered with silt. He scooped away worms, beetles, the opaque red pellets of pupating moths. He dug and dug and dug.Come, serpent, come–heal the pain.Often, he wept. Tears pushed up and out of him, beading clear and hot on his eyelids. Dirt on his tattooed cheeks would blacken them as they rolled down, darkly streaking his beard. Big, heaving sobs shook his chest. It was habitual in these moments for him to wail.Serpent, serpent, take this pain! Maja–He sat back, staring in.What did he see? What did he find?Maja?Nothing. Unfailingly, agonizingly, each time: nothing but rocks and dirt. He went by instinct, sufficed only when his tears stopped so he could see the small, desperate hollow in the soil carved out of hurt and ache. He never dug too far.But once there were tree roots, kaleidoscoping with fungi. Sometimes he found salt crystals and earthworms, or a cluster of snails in opaline whorls. Outside of Ala Gannha, beneath the pyramid canopy of an old urunday, he unearthed the curve of a dead carnivore’s jaw.There was always something there, never what he dug hoping to find.Depleted, exhausted, wholly empty of what he carried, he would fill up the hole. He packed in fistfuls until the recess evened out. He wanted it to look as if it hadn’t been recently disturbed. When he finished, he got up. He wiped his hands.

Some day, he would tell his brothers. He might even bring them–just one, or both, it didn’t matter. Where one went, the others went, too, in time. And if they had rituals of their own, he would observe them, listen; he might even join in. That was their nenna.He would be patient and understanding, their chronicler of the ways things are.

Connections and Hooks

Known

◆ 'Soldier, Poet, King'

Similar in look (but varying in lifestyle), the Eryut three wander far and tell each other's tales; while Rafi may not be known to you, it's quite possible you've heard of him through one of his siblings.

◆ My City Is Greater than Jewels

Following their banishment, the brothers Eryut traveled through Skatay and Dalmasca, only to settle in Thavnair. Though their jobs take them far, the brothers oft return to Radz-at-Han, where Rafi—least ubiquitous of the three—maintains the villa that has served as their familial home base. Maybe you've seen him in the markets, passed him during visits to your local chemist, or seen him down at the airship docks; maybe he's your neighbor. He and his brothers have lived there for over forty turns.

◆ Fossil Ferns and Antlers

Business and travel dominate a chunk of Rafi's connections. He is a business administrator for Pechika and Gur's Commodities, a Hannish geological and archaeological import company. P&G's contracts reach to Kugane, Ala Mhigo, Amajina and Son's Mineral Concern of Ul'dah, and the Gleaner's Guild of Old Sharlayan, so Rafi can conceivably be found in and around these locales.

◆ Diamonds, no Rust

Frequent trips to Thanalan led Rafi to pick up a second trade some twenty turns ago. He is known to the Goldsmith's guild next door to Eshtaime's Aesthetics, having achieved the rank of journeyman jeweler. Looking to commission a personal piece? He's happy to work for you, so long as you're fine with the guild price!

◆ Appetites for Chaos

As of Starlight, Rafi is a winner of the Calamity's End Bar and Grill's Primal Slayer Challenge. He conquered a five-ponze burger and the Broadside shot challenge without breaking a sweat. Look for him (and his brothers—namely Rudi, who didn't handle the Broadside very well) on the bar's Wall of Fame.

Furtive

◆ Exiled of Golmore

Some sixty turns ago, a fearless treeward warrior called Refr violated the Green Word when he committed a terrible sacrilege in the Wood. Though innocent of this arcane crime, his brothers Hrudr and Hrafn accepted his selfsame exile, and all three were banished from the Wood. For who wouldn't choose the trials of a cold and unfamiliar world, rather than know life apart from their beloved brother?

◆ The Green that Creeps

Many Viera who leave home discard their 'forest names': appellations or titles worn while living under the Green Word. While all three brothers retain Eryut as a surname, they prefer different 'city names': Hrudr has adapted to 'Rudi,' and Hrafn prefers the Dalmascan cognomen of 'Rafi.' (And then there's Refr, who, likely out of personal arrogance, changes nothing). Should another Viera dare to use his or Rudi's forest names, Rafi would aggressively investigate them further—either to silence them, or glean news from their far, forbidden home.

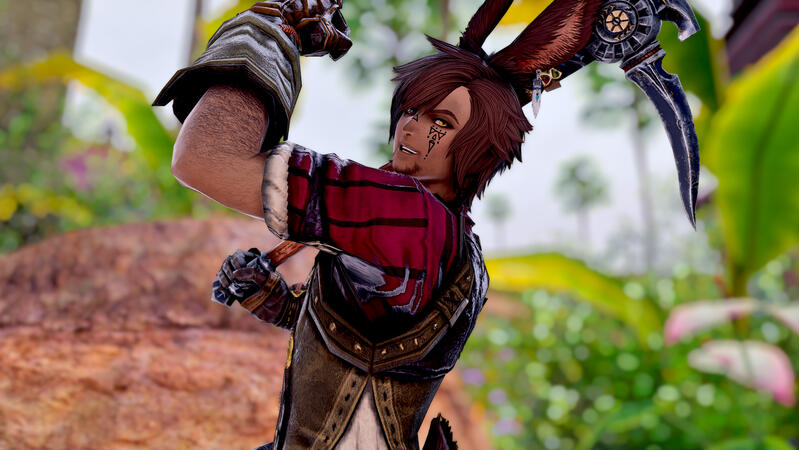

◆ I Studied The (Circular) Blade

Rafi is a talented physical combatant who put his woodward prowess to use in service to the Radiant Host. For some fifty turns, he has practiced the Hannish art of the chakram, meticulously devoting himself to learning techniques of the great masters of eld. His dedication has earned him the most precious of accolades: a Dancer's sacred stone.

◆ Dancer in the Dark

When the Imperial legions mobilized to conquer regions of the Near East, the Radiant Host employed Rafi as a clandestine field agent, sending him undercover to gather information and protect Hannish citizens far from home. His job with P&G provides the perfect cover for such delicate work: both an importer and a Hannish spy have need for travel, and plenty of reasons to excuse being anywhere at any given time.

◆ War and the Weary Heart

A sorrowful section in Rafi's history, one of which he rarely speaks. South of the One River—mere malms from his ancestral home—the jungles of Nagxia could not be easily captured by Garlemald's XIth Imperial Legion. Originally dispatched there for work, Rafi fell in with the Nagxian Resistance, where he aided local villages against Imperial attack. Members of the various Resistance forces might have heard of what happened at Dagluk and Bunlai; Rafi refuses to discuss either atrocity, even in the company of fellow Resistance veterans.

ᚺᚱᚢᛞᚱ

Rudi Eryut

⬥

Argues He's The Eldest of the Triplets (Which Tells You Plenty)

⬥

Strikes Like Lightning, Drinks Like A Fish

⬥

Former Fist of Rhalgr

⬥

Lejo Wolt

⬥

A Rava from Tepjala, Not Long Gone

⬥

Big Heart, Bigger Shared Single Braincell

⬥

Beloved Boyfriend (That Took You Guys A While...)

⬥

Aja Hyskaris

⬥

One of The Very Important Viera at the Bole

⬥

Cool, Tall, and A Little Daunting

⬥

More Guns, Bikes, and Style Than You

⬥

Lofn Yascaret

⬥

Another Very Important Viera at the Bole

⬥

Superb Culinarian and Businesswoman

⬥

Sky Pirate and Hot Sauce Goddess

⬥

Pjel Qoet

⬥

One More Very Important Viera at the Bole

⬥

Tough, Cool, and Enigmatic

⬥

Extremely Intimidating Mercenary

⬥

Petal

⬥

Once Pink-Haired, Always Pugnacious

⬥

Once Helped Steal a Cactus

⬥

A City Viera, Through and Through

⬥

Mayvis Kiernan

⬥

Mysterious Machinery Genius

(Or So He Thinks)

⬥

Frequently Frowning Bole Visitor

⬥

Cute Even When She's Cold

⬥

Skoenraet Elilfrut

⬥

"The Devil You Know"

⬥

Rough, Rowdy, and Reliably Chaotic

⬥

Secretly One of Pipi's Favorite People

⬥

Tide Wraith

⬥

A Laughing Terror from the Sea

⬥

Dirty Jokes, Dirtier Fighting

⬥

I Hear the Jaws Theme Playing

⬥

Etana Rahal

⬥

Cheery Priestess of Faram

⬥

The Food is Baked With Memories

⬥

Awakens Old Sentimentality for Rabanastre

⬥

Ianthe pyr Visellia

⬥

Etana's Clever Companion

⬥

Unbelievably Cool Tattoos

⬥

Down to Earth; Maybe a Defector?

⬥

Forestay Larchleg

⬥

Another Champion Culinarian

⬥

Sunny and Salty Sea Sailor

⬥

Will Absolutely Break Your Nose

⬥

Out of Character

they/them

30+; queer; frequently afk (sorry)

pacific time zone (PDT)

I am a selective, story- and development-driven writer with several years of experience in collaborative RP. If you're interested in writing with me and potential story involvement, feel free to send me a tell in-game.While FFXIV contains fantastical themes/tropes that lean into contemporary parallels (e.g., xenophobia, racism and related stereotypes, class inequality, misogyny, and many others), I will not engage with players or groups whose OOC conduct, character design, or roleplay I find offensive, insensitive, or otherwise unpleasant.Rafi is a trans man with he/him pronouns. As an nb person with my personal experience at the heart of my writing, I like talking about the impact of gender in his narrative, backstory, design, and within Golmore and greater Viera culture. As suggested on the right side of this page, I don't tolerate crude or otherwise shitty transphobic comments, questions, microaggressions, and any similar vibes from other roleplayers and/or their characters, and will block/blacklist because of them.Rafi and his brothers are the result of a collaborative RP project between three friends, planned prior to Endwalker's release. Our headcanons and creative elements of their tribe, culture, and history are primarily sourced from XIV lore, with hinting influence from the lore of the Viera from Final Fantasy XII.

THE GOOD STUFF ✓✓✓

lore/MSQ-adherent RP

slice of life

venues/events

comedic+combat

one-shots/'acquaintances'

LGBTQIA+ characters and themes

CHECK WITH ME FIRST ✓

pre-established backstory connections

business connections/trade

mid-length storylines

training/sparring

long-term relationships

homebrews and headcanons

WoLs and MSQ NPCs

NOPE ✕

characters and players under 18

godmoding, metagaming, metaposing, et. al.

poor IC/OOC boundaries

joke/meme characters

Bad vibes re: characters and scenes displaying IC ableism, racism, antagonistic behavior, and/or other insensitivities, pushy behaviors, and aggressions

ZERO PATIENCE FOR THIS ✕

IC or OOC homophobia, transphobia, associated slurs or derogatory language, TERFs, et. al..

carrd preview images of Yakushima Forest by

Raphael Oliver Photographytitle quote from In Fantasia

by Kishi Bashi